On this page

It often happens that you go to the supermarket to buy something specific and can't find it. It happens to me all the time... so today I was wondering: ‘How much do “missing” products affect turnover? And what is the impact of “slow-moving” items on margins?’

Unfortunately, there are no official statistics on this issue: when you think about it, when does a shop assistant or salesperson ever bother to note that a customer has asked for a certain product and not found it? And, especially in large retail spaces (supermarkets, hypermarkets), it is not even certain that the staff will be aware of this: the customer will simply opt for a different product or go and look for it in another shop.

The Traditional System (MIN/MAX)

However, estimates tell us that, on average, the number of “stockout” products, i.e. missing products, in a company can be calculated in a range between 10% and 25%, while the number of “slow-moving” products is around 30%.

This means that if the company had a turnover of £100 million, it could actually have a turnover of at least £125 million if it managed to eliminate the missing products. And it most likely also means that actual margin represents 80% of the potential margin, due to the proliferation of slow-moving products: if the same company in the example closed its financial statements with a gross margin of 10 million, that margin could potentially be 12.5 million, again assuming that it managed to eliminate slow-moving items.

Companies tend to solve this problem using methods provided by ERP systems, for example by setting minimum (MIN) and maximum (MAX) quantities for a product, defining the safety stock quantity, the minimum order value and the supplier's lead time for delivery.

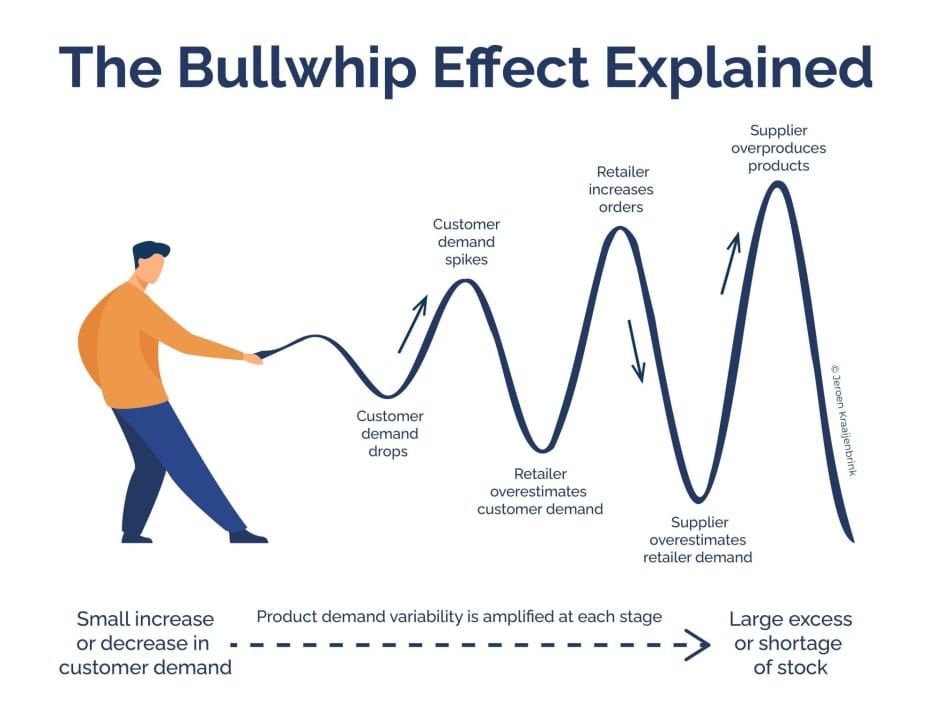

The Bullwhip Effect

Unfortunately, the algorithms provided by ERP systems, although valid, are unable to take into account changes in the markets (consumers change their tastes and opinions) and often vendor policies are such that they encourage the accumulation of unsold products: discounts for larger batches, for full loads, canvas, campaigns and so on. Not to mention phenomena such as the “bullwhip effect”, masterfully described by Peter Senge in his book “The Fifth Discipline”, where a small but unforeseen variation in end-user demand has an exaggerated impact on upstream distribution channels.

The Pull System

So, is there a solution? The answer is yes, by changing the supply model and switching from a “push” system to a “pull” system: the “trick”, if you wish to name it so, is to shift the focus from the forecast (which is inherently unreliable) to actual consumption (which is in its nature accurate) and utilise an algorithm that allows you to calculate the ideal stock value, which, in turn, will be managed using a different criterion, subject to frequent recalculations (even daily) to understand:

- whether to reorder

- the reorder quantity

- the urgency of the reorder

- whether and how to change the stock value

For any further information, please use the comments section or drop me an email... and don't forget to subscribe to my blog to receive all the updates directly in your inbox! 😊